The image of a witch has become one of Halloween’s most iconic symbols, complete with pointed hats, cauldrons, and broomsticks. In pop culture today, witches are depicted in all sorts of ways—from the mischievous and misunderstood to the malevolent and mysterious. But while dressing up as a witch can feel playful and spirited, the historical origins of this symbol carry a darker and more haunting truth. Just over 300 years ago, being called a “witch” could mean social ruin, imprisonment, or even death, especially for women who dared to defy societal expectations.

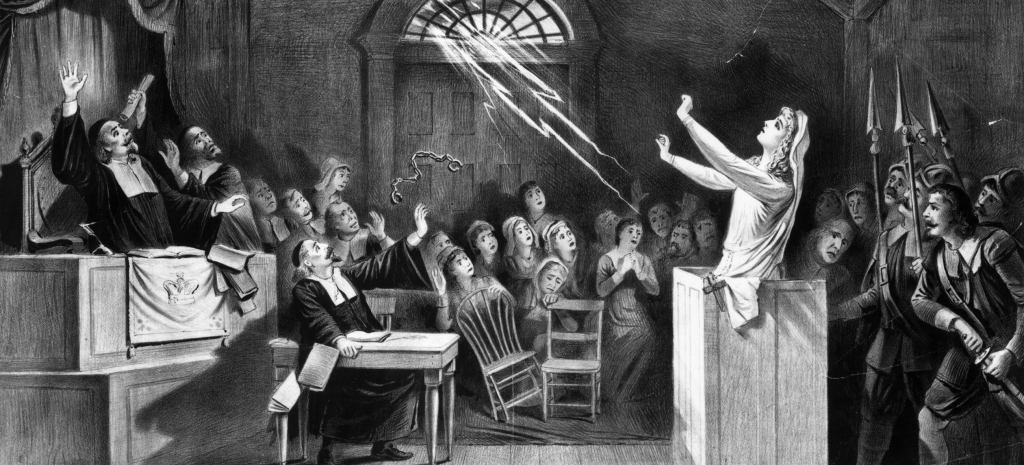

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 marked a feverish period when fear and suspicion rippled through the Puritan community of Salem, Massachusetts, leading to the tragic deaths of twenty people—primarily women—and the persecution of many more. These events weren’t just about punishing alleged “sorcery”; they reflected a powerful social structure where gendered fears, paranoia, and a need for control twisted into something nightmarish. As we prepare to celebrate Halloween, it’s worth reflecting on the history of the “witch” symbol and how it speaks to themes that remain deeply relevant today, especially concerning the treatment of women and the destructive nature of “othering.”

The Role of “Othering” in the Salem Witch Trials

In Salem, the concept of “othering”—the act of isolating or alienating those who didn’t fit the community’s rigid ideals—was weaponized to maintain social control. While “witch” was a blanket term, those accused shared certain characteristics: many were poor, independent, or outspoken women who didn’t fit within the traditional mold of a Puritan wife. Widowhood, poverty, physical disabilities, or an eccentric personality could quickly make one a target, as any deviation from the “norm” posed a perceived threat to Salem’s social order.

For example, Sarah Good, one of the first women accused, was in need of money, often begging for food. Her poverty and perceived strangeness made her an ideal scapegoat, aligning with Puritan suspicions that material hardship or desperation correlated to failing morals. The trials were as much about fear of social breakdown as they were about punishing supposed witchcraft. To the Puritan mind, the poor and unrepentant Sarah Good represented the disorder that could creep into their tightly controlled society if left unchecked.

The psychological underpinning here is clear: by labeling these women as witches, the townspeople could isolate and condemn them, upholding a sense of unity and moral superiority among themselves. This “othering” stripped women of their percieved humanity, reducing them to symbols of fear and sin. This pattern of isolating “outsiders” reveals a troubling tendency that extends beyond Salem, evident in how societies often react to individuals or groups who challenge established norms. Even today, the “othering” of individuals due to their beliefs, gender, or appearance persists, portraying how Salem’s trials hold a mirror up to modern fears and biases.

Spotlighting the Forgotten and Notorious Figures

Within the tragic list of those accused during the Salem Witch Trials, several women stand out not only for their alleged “crimes” but also for the ways in which they challenged societal norms.

Martha Carrier: Dubbed the “Queen of Hell” by her accusers, Martha Carrier was known for her bold personality and sharp tongue. Her outspokenness marked her as “dangerous,” and during her trial, she was subjected to wild accusations, including claims that she led a demonic army.

Carrier’s story underscores how women’s independence and confidence could easily be construed as threats. Her fate is a sobering reminder that, in a society that feared female authority, women who refused to submit were quickly silenced.

Bridget Bishop: A tavern owner known for her vibrant personality and choice of clothing, Bishop was another easy target. As an unconventional woman operating a business, she represented the type of self-reliance that Puritan society discouraged in women. Bishop’s lifestyle was considered provocative and rebellious, casting her as an outsider. Her story resonates as an example of how female economic autonomy was frequently demonized, both then and now.

Elizabeth Johnson Jr.: Elizabeth Johnson Jr. was one of the many lesser-known figures swept up in the hysteria, though her legacy is unique. In her early twenties, Elizabeth was accused of witchcraft alongside her mother and aunt, her crime tied to little more than gossip and hearsay. Despite the lack of credible evidence, she was convicted in 1693.

Elizabeth’s conviction, unlike many others, lingered for more than 300 years—she was not officially exonerated until 2022. Her late exoneration underscores how the “othering” from Salem’s past held a chilling endurance, taking centuries to be formally corrected. Johnson’s story illustrates the relentless power of “othering,” which not only impacts individuals in their lifetime but can also stain their legacy long after.

By examining these forgotten and notorious figures, we begin to see a pattern—those accused were often those who either lacked male protection, displayed autonomy, or stood outside the narrow definitions of “respectable” femininity. The trials thus reinforced a powerful social message: women who did not conform were dangerous and to be ostracized.

The Intersection of Gender, Fear, and Power

The gendered aspect of the witch trials cannot be overlooked. Salem’s trials turned women’s independence, assertiveness, and “otherness” into sins punishable by death. The Puritans lived in a deeply patriarchal society, and women who spoke their minds and controlled their own fates became seen as rebellious—almost supernatural threats. By labeling these women as “witches,” Puritan leaders could justify their actions as a moral necessity, veiling the gendered paranoia with a thin layer of religious piety.

This emphasis on women as dangerous outsiders also speaks to the double standards that continue to shape societies today. Even now, women who challenge societal expectations or refuse to comply with traditional roles often face backlash. While we may not hold literal witch trials, gender-based “othering” remains pervasive, whether in professional environments, social expectations, or cultural representations. The trials demonstrated an instinct to “other” and condemn anything that threatened social order, particularly if it came from women who held power or independence that the traditional authorities found unsettling.

The image of women as threats to stability is a deeply rooted bias that has remained relevant over centuries. Today, women’s assertiveness is often still seen through a lens of suspicion or disdain, especially when they claim spaces traditionally occupied by men or defy norms about “proper” femininity.

Beyond Witchcraft: Salem’s Warning for a Divided World

As we celebrate Halloween and reflect on the legacy of the Salem Witch Trials, it’s worth considering how these themes of othering and control still play out today. The trials remind us of the dangers of “othering” those who are different, a phenomenon that occurs in various forms across time. In Salem, fear of “otherness” led to hysteria, violence, and the loss of innocent lives.

What if society had, instead of giving in to paranoia, embraced differences and learned from those who saw the world differently? How many lives might have been spared if Salem’s townspeople had found value in the perspectives of those who didn’t conform? In our own time, these are pressing questions that speak to every community’s ability to create safe, supportive spaces—or to punish those who dare to defy the norms.

“Othering” often leads us to assign blame where there is none and to simplify complex people into stereotypes that confirm our fears. Salem’s history invites us to look within and recognize when we’re casting someone as “other” rather than understanding them. The trials serve as a stark reminder of the dangers of judgment, of letting the impulse to categorize others overshadow our shared humanity.

Perhaps Halloween’s legacy of witches, when reflected upon, is not simply to celebrate what’s dark and eerie, but to confront the ways we still fall prey to fear and prejudice, and to consider how we might redefine what it means to belong. By remembering the women of Salem who were unjustly branded as “witches” and the lives they led, we honor a part of history that warns us against the dangers of unchecked fear and collective hysteria.

This Halloween, as we revel in the imagery of witches and the supernatural, may we also keep in mind the courage of those women who lived, resisted, and endured as both symbols and victims of society’s fears.

Leave a comment